State: Ntl.

Fresh Thinking about Work Fatalities: [2015-02-02]

Traumatic work-related deaths are a rare tragedy in America. As measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 4,405 workers died on the job in 2013. We are far from the killing fields of a century ago, when Pittsburgh alone accounted for over 400 work fatalities a year.

Yet work deaths have not declined as much as non-fatal injuries have in the past two decades. Work injuries involving at least 31 days’ lost time have declined by 45% since the early 1990s, but work fatalities by only about 35%, from 6,210. Perusing year by year fatality tables, one has an uneasy feeling of a stalling in progress.

Going from, say, 6,000 to 3,000 deaths may call for a fresh perspective on what is causing them, starting with a more nuanced understanding of how fatalities have fallen (or not, for some jobs) in the past.

Causation of work fatalities is a complex issue, certainly more complex than the occupational safety literature usually recognizes. Causation stretches across a broad spectrum, from the individual actions of a worker, to the work environment, to the employer, and societal forces. Some years ago, I wrote a column in which I identified 10 factors that could contribute to a higher death rate of undocumented construction workers.

Fatalities may be declining as much from better medical response as from gains in prevention.

Doctors are very likely saving injured workers today who would have died before.

Trauma centers – hospitals with a special competence to treat victims of violence, falls, auto accidents, and such – have proliferated in the past few decades. A 2006 study documented an improvement in survival rates due to these centers. The occupational safety community doesn’t appear to have analyzed how better medicine may account for much of the decline in fatalities. Better trauma care in the future might still cut fatalities by hundreds a year.

The pace of improvement varies a lot. Question why.

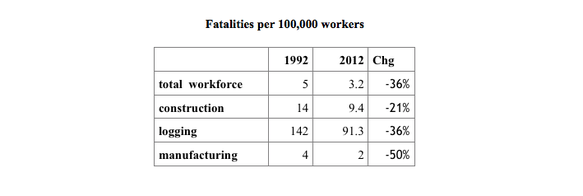

It’s commonsense that work fatalities can more readily be reduced where the work environment is more controllable. The table below shows that manufacturing fatality rate declined the most, probably because the worksites were more manageable. Logging may have been relatively deficient in safety in 1992 and therefore could catch up more than, say, construction.

Societywide forces, rather than work-related factors alone, are behind much of the decline in work deaths.

Consider homicides, of which there were over 1,000 a year two decades ago and now under 500. It’s hard to boast that worksite prevention helped to prevent these deaths when, according to the FBI, the rate of violent crimes in the country declined by 48% between 1993 and 2012.

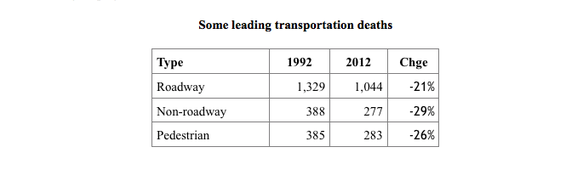

Transportation deaths, accounting for two out of every five work fatalities in the past 20 years, are in large measure a public safety problem. The rate of all traffic fatalities in the country dropped by about 40% over the two decades reported in the table below.

As the table below shows, over a thousand transportation deaths a year occur on public roads, where public safety factors such as traffic conditions affect driver safety. (Miles driven by large trucks increased by 75% during these years.) Work-related pedestrian deaths are largely (but not entirely) beyond control by employers. Non-roadway deaths, involving construction and other commercial private sites, are likely much more impacted by employer controls.

Causation of rare events must be relentlessly pursued.

Roughly 1,000 to 1,500 work deaths a year arise from sales, managerial, professional and other work in which by occupation the risk of death is less than two per 100,000 full-time workers. Are these freak, random accidents?

It’s prudent to avoid labeling any fatality, work related or not, as the result of a freak accident. Herbert Weisberg, a statistician and expert on causation, told me that what appears random to medical scientists may sooner or later become preventable. He cites the progression of AIDS from mystery to well understood and treatable condition.

About 20 pleasure sailors are reported to die annually (some cases are in all likelihood not reported). My brother John Rousmaniere, author of a classic account of the Fastnet yacht race in 1979 in which 15 crew members died, is firm that there are no freak accidents. He once investigated an electrocution by an overhead power line that touched a mast of a small boat on a boat ramp and uncovered other similar preventable incidents.

In order to significantly reduce traumatic work fatalities further, we can’t rely entirely on incremental thinking. We need to build a comprehensive strategy.